Restoring Atlantic salmon in the Clyburn Brook

Cape Breton Highlands National Park

Their story

Atlantic salmon are fascinating. They love both salt water and freshwater, they have a really strong sense of smell and they change colour! They also live for many years at sea and travel long distances to return home to spawn in the river in which they were born. However, they also face threats like disease, overfishing, climate change, and habitat loss. They are struggling to survive. They need a helping hand.

Parks Canada has been monitoring the adult salmon population on the Clyburn Brook in Cape Breton Highlands National Park for over 30 years and has noticed a sharp decline in the population in that river since 1995. The numbers over the years show the tale of a struggling species.

For Atlantic salmon, mortality between the smolt stage and adult stage (when they are in the ocean) is high, so it is very important to compare how many fish go out to the ocean as smolt and how many come back as adults. Without spawning fish, the salmon population in the Clyburn Brook cannot maintain itself, and the population will disappear.

The project

Atlantic salmon in the Clyburn Brook are endangered. Counts of adult salmon have shown that the population in this river has declined by over 95% since 1991. As a recognized leader in conservation, Parks Canada is taking action to contribute to the recovery of Atlantic salmon in the Clyburn Brook.

Working with partners including Mi’kmaq, academia and others, we are implementing a salmon recovery strategy. This aim of the strategy is to increase the spawning adult salmon population and restore the aquatic ecosystem of the Clyburn Brook.

Over the five-year project (2019-2024), Parks Canada is carrying out research to estimate population size at different life stages, mapping available salmon habitat and conducting genetic analysis to better understand diversity in salmon populations within and across rivers in the park.

In addition, this project will re-establish wild juveniles and increase adult natural returns working closely with Dalhousie University. Wild-origin juvenile salmon are being collected from the Clyburn Brook and then transported to the Dalhousie Aquatron Laboratory, a fish-rearing facility. Atlantic salmon are being reared to adulthood in this facility and then transported to the Clyburn Brook to be released.

Connecting the project with Canadians and visitors to Cape Breton Highlands National Park is a key project deliverable. Parks Canada is developing new visitor experiences and public engagement activities to help increase awareness and knowledge of the plight of salmon.

Cape Breton Highlands National Park is collaborating on a regional scale working alongside four other national parks in Atlantic Canada as well as with Indigenous partners, academia, stakeholders, and all levels of government to coordinate efforts to restore Atlantic salmon to the Clyburn Brook. For more information on the regional project Atlantic Parks Salmon Recovery, please visit Atlantic parks salmon recovery.

A Five-Step Process

This five-year project on the Clyburn Brook involves collecting wild-origin juvenile salmon and raising them in captivity to increase the spawning adult salmon population in the river. This is a comprehensive five-step process:

-

Collection of smolt during spring run (May-June)

From mid-May to late-June, our team collects juvenile salmon (smolts) from the Clyburn Brook for transport to Dalhousie Aquatron Laboratory. The salmon are captured using fyke nets so they can be counted and prepared for transport to the fish-rearing facility. Once captured, the salmon are kept in a holding tank in their habitat prior to transport.

Smolt run

Smolt run -

Collected smolt transported to Dalhousie Aquatron Laboratory

The Dalhousie Aquatron Laboratory (Aquatron) is a world class aquatic laboratory and the largest university-owned aquatic laboratory in Canada. The Aquatron works with a range of clients from around the world, including professors and students from Dalhousie University, government and private companies from a range of sectors.

Trained technicians from the Aquatron transport the fish from Cape Breton Highlands National Park to the Aquatron in Halifax. When the fish arrive at the Aquatron, they are carefully introduced to their new tanks to keep their stress at a minimum. As the fish are wild, the next step is to teach them to eat food provided by Aquatron staff. The fish are monitored by fish health staff who report to the university’s veterinarian.

Smolt raised to adulthood

The Aquatron has different facilities, including many small wet labs and large seawater tanks. Some of these tanks are the same volume as Olympic swimming pools.

The Atlantic salmon from Parks Canada are kept in two of the specialized wet labs. Each wet lab is equipped with holding tanks where the salmon live. The wet labs and tanks are supported by specialized Aquatic Life Support Systems (ALSS), which control and treat the water quality for the fish. The ALSS for each lab can control the water temperature, flow rate and other parameters to keep the fish safe. These systems are computerized and can communicate with Aquatron staff 24 hours a day. In the event of an unwanted change in the system, technicians are notified and respond immediately.

A project of this kind requires specific needs from a unique partner that can help grow the salmon population. This includes a biosecurity plan, access to a veterinarian, ability to control water parameters and quarantine capabilities. Parks Canada is pleased to be working with Dalhousie University’s Aquatron Laboratory with the added benefit of having a variety of academic researchers close by who we can engage in the project.

Adult salmon released in Clyburn Brook

When the salmon are fully mature, they are released back into the Clyburn Brook. In this river, the wild salmon return in late fall, usually November. Salmon raised in Dalhousie University’s Aquatron and ready for release are reintroduced to the river at this time as well. They travel from the Aquatron back to their home in the Clyburn Brook and up the river in a holding tank.

To ensure they have a smooth transition, we select a location with deep pools and lots of hiding places to release them. It will have been over a year since the salmon were in the river, and they need time to explore and get comfortable!

The release process looks quite similar to the way you add a new fish to an aquarium. Water from the river is gradually added to the holding tank so the fish can get used to the new conditions. When the water chemistry in the tank matches the river, the salmon can be safely placed back in the stream. Conservation staff monitor them for a while. Finally, we wish them good luck as they swim away and join the other salmon in spawning.

We hope to see these salmon again during future swim counts, and to find their offspring while collecting juveniles.

Counting adult salmon

The resource conservation team at Parks Canada in Cape Breton Highlands National Park has been swimming with the salmon on Clyburn Brook since 1985. Every fall, adult salmon return to spawn in the river. The team waits for the right conditions to swim on the surface of the water and use dry suits and snorkels to count salmon below.

Counting adult salmon that make it back to spawn is critically important for monitoring the health of the salmon population. Without spawning fish, the salmon population in the Clyburn Brook cannot maintain itself, and the population will disappear.

The team also monitors the number and body condition of juvenile fish in the river. This allows them to see changes in the population throughout the life cycle.

Swimming with salmon

Swimming with salmon

Life cycle of an Atlantic salmon

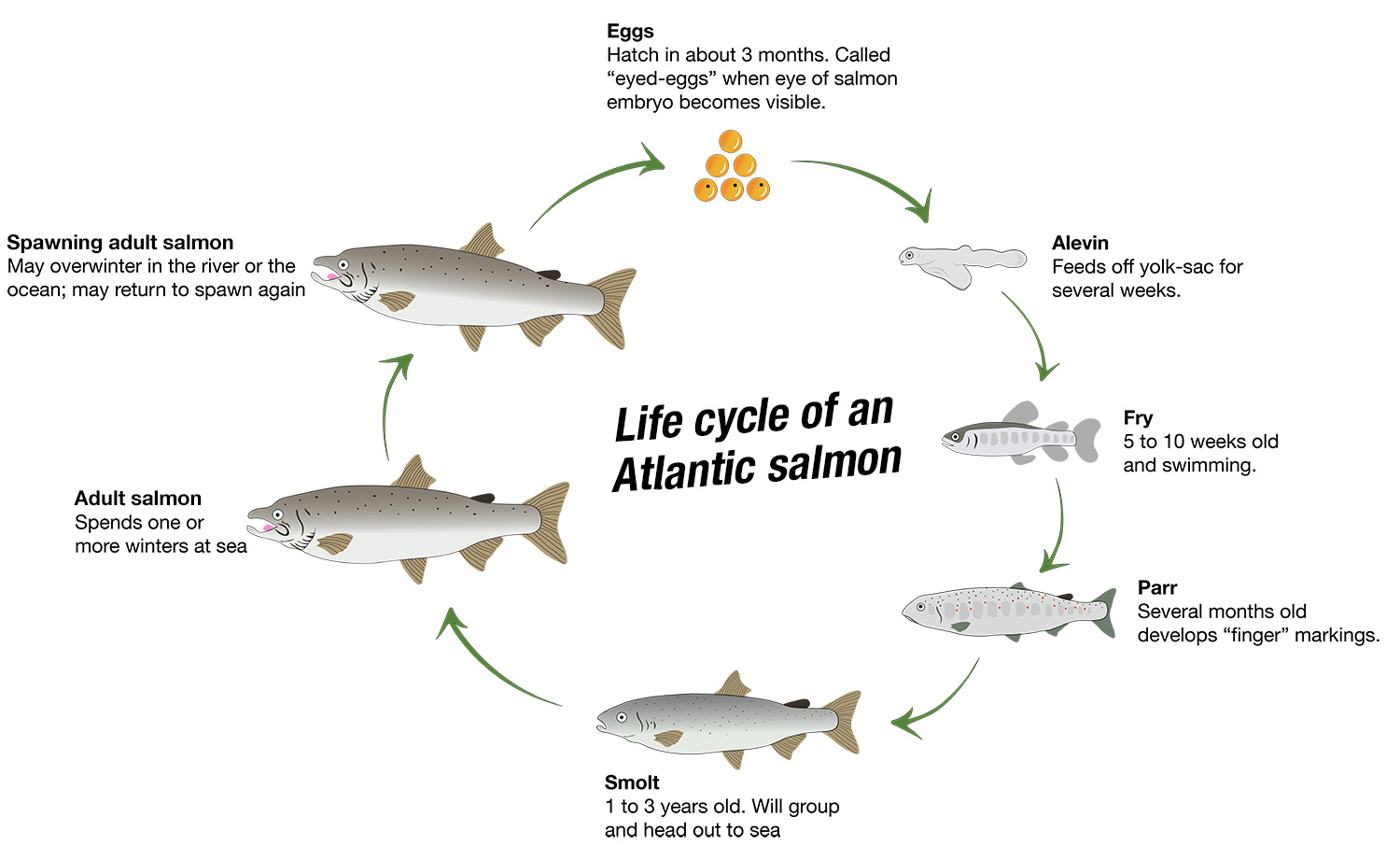

Did you know that the life cycle of an Atlantic salmon includes seven stages? It’s true. They are: egg, alevin, fry, parr, smolt, adult and kelt.

Egg – Salmon start out as small round orange eggs in freshwater rivers. They often seek protection under small rocks.

Alevin – After several months, the eggs hatch into small salmon called alevins. They hide under the gravel to keep safe from predators.

Fry – After four to six weeks, alevins enter the fry stage. They're still tiny but leave their home under the gravel and start eating tiny creatures.

Parr – Once they’re a year old, salmon enter the parr stage and live in freshwater rivers for one to five years. They eat insects and grow to about the length of a crayon.

Smolt – The salmon grows into a smolt between 11.43 – 24.13 cm long. They swim downstream to where the river meets the ocean in a mixture of freshwater and saltwater.

Adult – As adults, salmon live in saltwater seas and oceans. They swim hundreds of miles, eating smaller fish and gaining weight. After several years, between April and November, they return home to the freshwater river where they were born. This is no easy task; they have to swim upstream, against the current, to spawn.

Kelt – A kelt is a salmon that has spawned the previous fall and over-wintered in the river. In the spring, they migrate back to the ocean after the ice melts.

Get involved, learn more!

For more information on the salmon restoration project at Cape Breton Highlands National Park, please contact cbinfo@pc.gc.ca or 902-224-2306.

Learn more:

- Date modified :