The aquatic restoration team at Riding Mountain National Park onboard an electrofishing vessel

Invasive species: aquatic ecosystems under stress at Parks Canada

Invasive species are one of the biggest threats to biodiversity in the world. This is especially true in aquatic environments. Parks Canada and partners are using innovative ways to tackle aquatic invasive species.

Learn how Parks Canada and partners are using a creative twist on spearfishing to remove invasive fish at Riding Mountain National Park in Manitoba:

Text transcript

[A diver wearing a wetsuit leans backwards off of a dock and falls into a lake.][The diver swims along the surface of the water while wearing a snorkel mask and holding a spearfishing device.]

[Parks Canada logo]

[The diver dips down closer to the lakebed and uses the spearfishing device to spear a Smallmouth Bass.]

Yeah!

[They hold the bass triumphantly above the water.]

Oh, it's a big one! Look how big that is!

[Diver shows the bass to colleagues back on the dock.]

[Title] Field Notes: Spearfishing for Invasive Smallmouth Bass, Riding Mountain National Park

[Parks Canada staff and partners drive a small boat to their early-morning spearfishing location.]

[Michele Nicholson speaks directly into the camera.]

Hello! My name is Michele, and I'm an aquatic ecologist in Riding Mountain National Park, in Treaty 2 territory in southwestern Manitoba.

[A map appears, outlining the boundaries of Riding Mountain National Park, with a label identifying Clear Lake on the map.]

And we are out on the lake; this is beautiful Clear Lake, and we are out doing some spearfishing today for invasive Smallmouth Bass.

[An illustration of a Smallmouth Bass appears in the bottom right corner.]

We have a new project this year where we are trying out a new technique to control an invasive fish that we have in Clear Lake.

[Parks Canada scientists pull snorkel masks over their faces, preparing to enter the water.]

A couple of years ago we got reports from anglers that they were starting to see and catch Smallmouth Bass in Clear Lake, and that was a big concern for us because Smallmouth Bass are not native to Manitoba at all, let alone Clear Lake.

[The scientists lean backwards off of the boat to enter the water. The lakebed appears and one of the scientists, Natalie, is snorkeling along the surface of the water.]

They're a really aggressive top predator fish, and they eat a lot of other fish, which can reduce their populations.

Local First Nations have fishing rights for Clear Lake, so that's something that we definitely want to protect, but we also want to protect the ecosystem of Clear Lake in general.

Spearfishing has been used in the ocean for controlling invasive fish but it hasn't really been looked at in freshwater systems.

[One of the scientists dives below the surface of the water and spears a fish. They swim to the surface of the water and hold up the speared fish triumphantly.]

Woohoo!

[Name Tag] Dean Martin, Resource Conservation Assistant, Riding Mountain National Park

It's a really cool project. We're partnering together with local First Nations to try out a new technique for protecting Clear Lake.

[Dean holds up a speared Smallmouth Bass to show the camera.]

[An aerial shot shows two snorkelers swimming in the clear water of Clear Lake.]

[Name Tag] Alex Prudhomme, MSC Candidate, Thompson Rivers University

[Name Tag] Natalie Vachon, Environmental Science Student, Brandon University

[Natalie and Alex speak to the camera while floating in the water wearing their snorkeling gear.]

So we are doing some recon trying to find Smallmouth Bass, and once we have observations, we also find nests of bass.

[A visible depression in the lakebed surrounded by rocks appears on the screen.]

[Label] Smallmouth Bass “nest”

Once they are confirmed, we capture the bass using spearfishing

And then we take some measurements on the effort, how much time it took, and also some nest measurements.

[Alex takes underwater photos of the Smallmouth Bass nest. Another Parks Canada employee records information back on shore.]

[Text] Spearfishing targets bass that are guarding nests. This allows predators to remove the remaining fry (baby bass) naturally.

[Camera moves toward a Smallmouth Bass nest, which has a tape measure laid across it.]

[A scientist spears a bass underwater.]

[A Parks Canada employee and a local community member ride on the boat back to shore.]

[Michele speaks into the camera.]

So what happens when this research is done?

[Camera shows an aerial view of Parks Canada scientists and local partners sitting at tables outside. They are measuring Smallmouth Bass, taking samples, and recording the data.]

Well, after we finish the fieldwork we are going to have to do identification on all of the stomach contents from these fish so we can accurately determine what

they've been eating, we will send away our aging samples to a lab where they will tell us how old these fish are, we'll be crunching all the numbers … after that, we can use the information

[Location Tag] Clear Lake 61A Reserve, Keeseekoowenin Ojibway First Nation

To figure out where we want to go from here. All of these decisions are really going to have to be made, collectively, though, with local First Nations.

We want to make these decisions together

[Three photos of local First Nation partners working together with Parks Canada on the Smallmouth Bass project appear on screen.]

And work together to determine the future directions of how we're going to manage invasive Smallmouth Bass and protect the health of Clear Lake together.

[Scientists float in the water, searching for Smallmouth Bass.]

[Text] By reducing the number of Smallmouth Bass in Clear Lake, we can prevent damage to the aquatic ecosystem.

[Timelapse of scientists unpacking the boat onto a dock as a the sun sets behind them]

[Text] Learn more about how Parks Canada is managing aquatic invasive species here: parks.canada.ca/ais

[Parks Canada wordmark]

The stress of it all

Aquatic invasive species cause harm to freshwater and marine ecosystems and the native species that live in them. For instance, aquatic invasive species put stress and pressure on the ecosystem in many ways.

They can outcompete native species for resources and can mate with native fish causing interbreeding. In addition, through intense predation, aquatic invaders can change the natural structure of the food chain.

The European Green Crab is one of the most invasive aquatic species in the world. They often destroy eelgrass habitat and harm the environment. Parks Canada found European Green Crabs in parts of Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Haida Heritage Site. Watch how Parks Canada and the Council of the Haida Nation is monitoring and removing this invasive predator.

Controlling Invasive European Green Crabs at Gwaii Haanas in British Columbia

Text transcript

[A Parks Canada vehicle drives down a dirt road, towing a research vessel on a trailer.]Parks Canada logo

[Parks Canada and Council of the Haida Nation resource conservation employees prepare the boat for launch at the dock.]

Government of Canada logo and Haida Nation Logo

[Charlotte and Chavonne speak to the camera while standing in the research boat, floating near a rocky shore.]

[Name Tag] Charlotte Houston, Resource Management Officer, Parks Canada

[Name Tag] Chavonne Guthrie, Resource Management Technician, Parks Canada

My name is Charlotte and I'm a resource management officer.

My name's Chavonne and I am a resource management technician.

We work in Gwaii Haanas, a national park reserve, national marine conservation area reserve, and Haida heritage site.

Title: Controlling Invasive European Green Crabs, Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, National Marine Conservation Area Reserve, and Haida Heritage Site

[Scenic images of the blue water and green mountains in Gwaii Haanas flash across the screen.]

[Resource conservation employees Charlotte, Chavonne and other team members drive the boat to the research location in Gwaii Haanas.]

Gwaii Haanas is co-managed with the Haida Nation.

This week we're working with the European Green Crab research team from the Council of the Haida Nation.

[Text] The European Green Crab is one of the most invasive aquatic species in the world.

[Gin prepares crab traps at the back of the research boat.]

[Name Tag] Gin Kampen, European Green Crab Response Assistant, Council of the Haida Nation

So, Gin, what are we looking for?

[Gin speaks to the camera while still preparing the crab traps.]

We're looking for European Green Crab, which are invasive to Haida Gwaii.

[A Green Crab crawls across a wooden dock.]

[Text] Ts’a’ám SG̲énuwaas | Tllga jii.nga sda k̲’uust’an k’inhlG̲ahl | European Green Crab / Carcinus maenas

They're really bad for the environment because they often destroy eelgrass habitat.

[Eelgrass sways gently underwater.]

And what they tend to do is snip the eelgrass and burrow into the mud banks underneath, causing instability in the eelgrass bank.

[The next shot reveals a section underwater where the eelgrass has been removed and the mudbank underneath is exposed.]

This is bad because eelgrass is like a nursery for a lot of our native species, like Pacific Herring and salmon, and octopus and many other species.

A photo of Pacific Herring appears.

[Text] Pacific Herring /Clupea pallasii

[A photo of Pacific Salmon appears.]

[Text] Pacific Salmon /Onbcorhynchus

[A video of a Giant Pacific Octopus crawling along the ocean floor appears.]

[Text] Giant Pacific Octopus / Enteroctopus dofleini

[Native Purple Shore Crab crawl along the bottom of a crab trap.]

[Text] Native Purple Shore Crab / Hemigrapsus nudus

They also outcompete our native shore crabs and juvenile Dungeness.

[A photo of a Dungeness Crab appears.]

[Text] Dungeness Crab / Metacarcinus magister

So they're pretty harmful for our environment.

[A woman standing on the bow of a boat drops a crab trap into the water.]

[Text] Traps are laid in areas that resemble typical Green Crab habitat. In 24 hours, they will be checked for crab and logged for data purposes.

[A woman drives a boat to the next crab trapping location. Another woman prepares crab traps.]

[Chavonne tosses a crab trap into the water while standing on the front of an aluminum boat.]

[Chavonne, Gin and another Parks Canada employee stand on the front of the boat while Chavonne speaks into the camera.]

It's day three and yesterday we got some bad news.

Previously, we had not found any Green Crabs in Gwaii Haanas, but yesterday we found some in Echo Bay.

So that's really sad to find.

[Gin makes a “thumbs down” gesture toward the camera.]

And then another devastating thing is one of the bears got one of our traps.

[The other Parks Canada employee holds up a flattened crab trap.]

It’s a little bit crushed.

But hopefully just in that one location, we find them so we can mitigate their impacts.

Fingers crossed.

[Gin lifts a Hairy Shore Crab from a crab trap and brings it toward the camera.]

So this is a Hairy Shore Crab.

[Text] Hairy Shore Crab / Hemigrapsus oregonensis

He's got hairy legs and he's one of the "good guys" native to Haida Gwaii.

[Gin reaches back into the crab trap, pulls out a Green Crab and shows it to the camera.]

And it actually looks like we caught a Green Crab, which is really sad.

[Text] Ts’a’ám SG̲énuwaas | Tllga jii.nga sda k̲’uust’an k’inhlG̲ahl | European Green Crab / Carcinus maenas

This is the first Green Crab that we've caught here in Slim Inlet, here in Gwaii Haanas.

So, yeah, as you can see on either side of its eyes, it has five points.

[A photo of a Green Crab appears. Labels appear, labelling each of five points on either side of its eyes.]

If you look at the shape of the carapace, they're quite different.

[Two images appear on screen. One of a Purple Shore Crab labelled “Native - Purple Shore Crab / Hemigrapsus nudus"]

[The other image is of a European Green Crab, labelled “Invasive - Ts’a’ám SG̲énuwaas | Tllga jii.nga sda k̲’uust’an k’inhlG̲ahl | European Green Crab / Carcinus maenas"]

The shore crabs are often like square or rectangular, whereas the Green Crab has more of this pentagonal shape.

[Aerial images showcasing the islands and blue waters of Haida Gwaii flash across the screen.]

[A gloved hand holds a Purple Shore Crab in front of the camera.]

[Text] Purple Shore Crab / Hemigrapsus nudus

[Chavone laughs at herself as she attempts to begin filming a scene, but accidentally captures herself in the video.]

[Laughing] I flipped it.

[While standing on the front of a boat, Gin holds a Green Crab in one hand and a measuring device in the other.]

So now that we found Green Crabs, what is the next thing that needs to happen?

We're going to be recording the size and the sex of the Green Crab,

and then we're going to remove it from the marine environment.

[Aerial footage of a rocky islet in Gwaii Haanas appears.]

[Text] Once European Green Crabs Establish themselves, it’s nearly impossible to remove them completely—but we can mitigate their impacts on the ecosystem.

[Text] This was the first joint expedition between Gwaii Haanas and the Council of the Haida Nation to monitor the European Green Crab’s arrival.

[Text] Together, we will continue to mitigate the invasive species impact.

[Aerial footage of a tree-filled island moves across the screen.]

Parks Canada logo

Government of Canada logo and Haida Nation Logo

Eelgrass is an ecologically significant species and an important habitat for fish and other marine life. Eelgrass even mitigates climate change by storing “blue carbon”. That is why Parks Canada works to protect eelgrass beds and restore eelgrass after it's been degraded by aquatic invasive species.

Learn more about what Parks Canada has done to prevent European Green Crabs at Kejimkujik National Park Seaside in Nova Scotia:

Text transcript

Parks Canada beaver logo appears[Music]

An illustrated map of Nova Scotia appears, with a place marker over top of Kejimkujik National Park Seaside.

[Text] Kejimkujik National Park Seaside

The camera zooms into a lake in Kejimkujik National Park Seaside. A label appears in the top left corner, indicating the year is 1986.

The lake is covered almost entirely with Eelgrass. An accompanying label indicates, “100% Eelgrass”.

[Text] Pre-Green Crab Invasion

Green crabs float beneath the water amongst the Eelgrass.

[Text] Green Crab Arrival

The date on the map of the lake changes to 1987.

[Text] Decrease in Eelgrass due to Green Crab invasion

The years in the top left begin scrolling rapidly to indicate the passage of time until the year 2009. As the years pass, the amount of Eelgrass covering the lake decreases from 100% in 1987 to 4% in 2009.

[Text] Green Crabs removed

A number counter appears and begins to increase, indicating the number of Green Crabs that have been removed from the lake between 2009 and 2016.

By the year 2016, 1,743,951 crabs have been removed from the lake.

As the number of crabs removed increases, the percentage of Eelgrass increases alongside it.

[Text] 34% Eelgrass restored from 2010 to 2016

Eelgrass sways gently underwater as small fish swim through it.

Parks Canada logo appears

These actions help the marine environment recover.

Unwanted guests

Aquatic invasive species often arrive in new environments by accident. For instance, the Zebra Mussel and the European Green Crab can “hitchhike” on boats to a new waterbody.

Text transcript

These hitchhikers are destroying ecosystemsZebra mussels are clinging to boats, canoes, kayaks and beach toys

Unknowingly transported from lake to lake

Riding Mountian National Park is monitoring lakes to ensure they remain free of such species

In 2017, Whirpool Lake tested positive for zebra mussel Environmental DNA

A decision was taken to close access to the lake and surrounding camprounds

This approach follows international standards to prevent the spread of invasive species

So far no mussel larvae have been found

Park Canada staff are inspecting all watercraft in the park

And are decontaminating them when necessary

Have your beach gear inspected and protect the lakes you love

Riding Mountain is beautiful

Let's keep it that way

Like. Comment. Share.

pc.gc.ca/parksinsider

Some species, like the Brook Trout in the Rocky Mountain national parks, were introduced for recreational fishing. This was at a time when the impacts of Brook trout on the ecosystem were less known.

Aquatic invasive species can be parasites, like Whirling Disease, which can seriously harm fish. Aquatic invasive species can also be plants, like non-native Eurasian Watermilfoil, Phragmites, and Cattails.

Restoring the marsh at Point Pelee National Park

Select images to enlarge

High costs

It's not just environments that suffer. Aquatic invasive species can negatively impact human social and cultural values. This includes access to water for boating, Indigenous harvesting, and recreational fishing. Fisheries are harmed when invasive species prey on native fish that people like to catch.

Some invaders can even force a closure of a beach, lake, or boat launch, preventing its use and enjoyment.

Preventing the introduction and spread of aquatic invasive species is expensive. Yet prevention is far less expensive than controlling, managing and monitoring once the invading species is established. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure!

Read on for 3 short stories about this work

-

Time to get creative at Riding Mountain

Manitoba

In 2020, anglers at Riding Mountain National Park alerted staff to Smallmouth Bass in Clear Lake. As a top predator, invasive bass can outcompete other fish. They also eat them, reducing their populations.

Clear Lake

Clear Lake (Noozaawinijing / Wagiiwing) is considered sacred by local Anishinaabe people and their ancestors. It is an important place where Indigenous Peoples harvest.

Keeseekoowenin Ojibway First Nation (KOFN) has been harvesting fish from the lake for many generations. Since the return of Clear Lake Indian Reserve 61A to KOFN, tradition and ceremony have also returned. Women have resumed their ancestral role as caretakers of the life-giving waters around the lake.

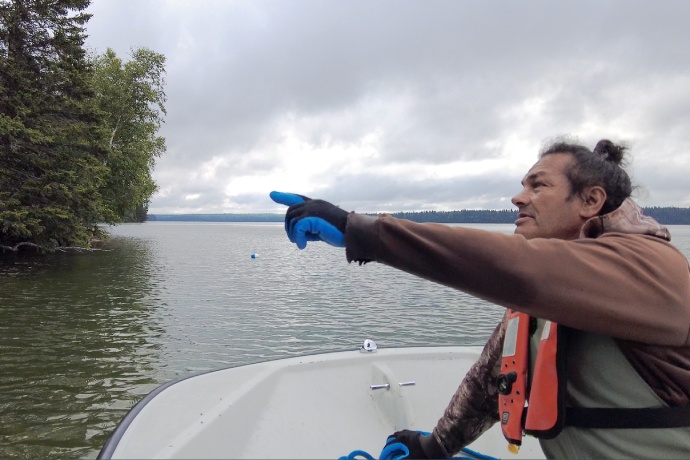

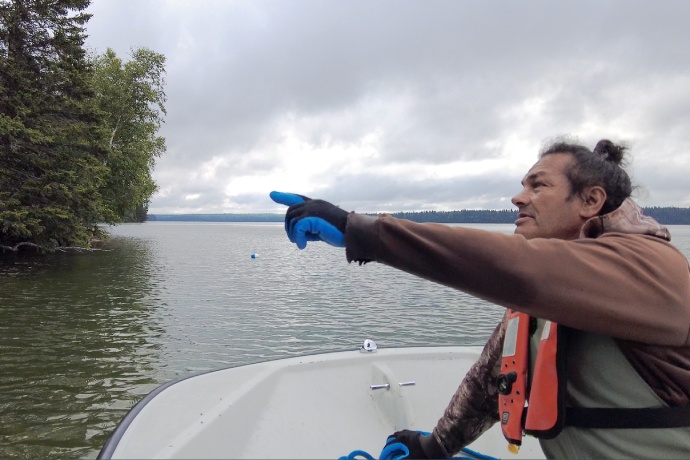

Local KOFN community member, John Sportak, shares his knowledge about Clear Lake with Parks Canada staff

John is removing a crayfish trap while monitoring Clear Lake. Invasive Smallmouth Bass feed on crayfish that native fish rely on for food The lake is sacred. We have ceremonies there. We try to remember the traditional ways so they’re not forgotten. Clear Lake is important to the future of my children. I have a responsibility to practice conservation of the lake. I want it to be there for at least the next seven generations.

Carolyn Brazeau and John Sportak at a kick-off celebratory feast and drum ceremony on their ancestral lands

Parks Canada staff and KOFN community members get ready for a day of field work Clear Lake is special ecologically. The lake is also a major draw for visitors as well as recreational boaters and anglers.

White Sucker fish migrate to a river from Clear Lake. Photo: Sean Frey/Parks Canada .jpg)

Kayakers enjoy using Clear Lake for recreation For these reasons, Parks Canada staff and KOFN have a shared interest in protecting Clear Lake from aquatic invasive species.

Solving the problem

In 2021 and again in 2022, Parks Canada and KOFN united to remove Smallmouth bass using electrofishing. Electrofishing does not kill fish, it briefly stuns them.

Over this time, any fish that were stunned were captured with a net. The crew counted and measured the native fish before releasing them back into the water. The bass were then humanely euthanized and kept for science.

Parks Canada staff on Clear Lake ready to remove invasive Smallmouth Bass

Parks Canada staff and Indigenous partners using electrofishing to remove invasive species Members of KOFN were generous in sharing their time and knowledge with Parks Canada. This included knowledge of the Clear Lake ecosystem, relationships between species, and fish behaviour at certain times of the year.

The electrofishing boat was also fully staffed in 2022 with members of the local Anishinaabe community. This helped to build relations, skills, and trust in the process.

Parks [Canada] were very appreciative of my knowledge that I learned from over the years. It was very good to be recognized for our life learning as cultural and traditional people. Everyone’s talking about Reconciliation. With that relationship building, I can actually see it happening. It opens doors and opens understanding.

Despite these efforts, electrofishing did not work for removing the larger, reproductive bass. Male Smallmouth Bass build and guard nests in shallow waters. If these “guardian fish” are removed, the nests are likely to fail.

History in the making

Parks Canada staff, along with two students from Thompson Rivers University and Brandon University, as well as members of KOFN, designed a pilot study to remove these bass using spearfishing. Spearfishing has been used to control invasive fish in the ocean, but rarely in freshwater systems.

From a boat, the crew flew a drone over Clear Lake to identify and locate the nests. Spearfishers then swam toward the nest. Within minutes of entering the water, the spearfishers were often successful at removing the guardian fish.

Select images to enlarge

A valuable opportunity

Smallmouth Bass caught by electrofishing were measured and examined by KOFN community members and Parks Canada staff. They wanted to understand the age, sex, and diets of the invasive bass.

Parks Canada applied cutting-edge research to support some of this work. Staff used DNA testing of bass feces to find out what the fish ate. By learning how bass are impacting other fish, staff and KOFN can decide how best to protect Clear Lake—together.

Parks Canada staff and KOFN community partners process the invasive fish on land. They collect data on the fish for science

This information helps them understand the invasive fish population Keeseekoowenin Ojibway First Nation shared Traditional Knowledge with Parks Canada staff on cleaning, cooking, and preserving the fish, as well as its cultural uses. All of the edible parts of the fish were given to local First Nations, so nothing went to waste.

This was a valuable opportunity for people from the [KOFN] community and staff to take part in science, share knowledge and learn together. Each day opened with a prayer and tobacco offering, led by a [KOFN] community member. It was a great way to start the work and pay respect to the people who have always been there.

Conservation staff worked with park law enforcement to amend fishing permit regulations. The change allowed anglers to catch more Smallmouth Bass. This empowered anglers to be a part of the solution of removing aquatic invasive species.

-

Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site

A world’s first at Kejimkujik

Nova Scotia

Keep out

Chain Pickerel are an invasive freshwater fish in Nova Scotia. They were found in Kejimkujik in 2018. It only took a few years before these invaders spread throughout its waters.

Chain Pickerel are voracious predators and out-compete native fish for food. They eat almost anything in the water, including fish, reptiles, frogs, dragonflies, and even ducklings!

Parks Canada staff had to stop the Chain Pickerel from spreading further, and prevent other invasive fish from entering. So in 2019, staff built two fish barriers. These modular barriers were useful tools for reducing the movement of invasive fish. Parks Canada found this technique useful for managing smaller, closed aquatic systems like lakes.

Staff monitored areas immediately downstream of the barriers in peak fish migration times. Where needed, Parks Canada helped native fish cross the barriers.

Modular fish barrier at Cobrielle Brook in Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site Efficient conservation

Once the Chain Pickerel were contained, staff could remove the invasive fish. Kejimkujik staff bought the world’s first electric-powered electrofishing boat as a powerful tool for surveying and removing the invasive pickerel.

We had past successes working with provincial counterparts using an electrofishing boat for removing invasive fish. Purchasing this equipment ourselves was an opportunity to invest in greener technology and for greening our operations.

This boat helps increase Parks Canada's capacity to remove invasive fish all while reducing greenhouse gas emissions by using a cleaner and quieter electric engine.

.jpg)

The electric powered electrofishing boat at Kejimkujik

Staff remove the invasive Chain Pickerel from the freshwater ecosystem How anglers can help

The prized crest is given to anglers at Kejimkujik who contribute their catch data for research Conservation staff also worked with site law enforcement. Together they created new rules that required anglers to release all the native fish and keep all invasive ones.

Team members also developed an angler diary program to tap into the experiences and observations of recreational anglers at Kejimkujik. The program resulted in hundreds of hours of data each year that Parks Canada uses to inform freshwater ecosystem management.

It also created a dialogue: the program serves as an engagement tool to talk about aquatic invasive species. Anglers are given a crest each year they return their diary.

This highly successful initiative has been met with lots of enthusiasm. Freshwater stewards are “angling” for their highly-prized crest each year!

-

Environmental DNA

We know you’re in there

eDNA

Only when a species is detected, can it be mapped and removed. One way that Parks Canada is using innovative technology to detect aquatic invaders is through environmental DNA (eDNA).

Detecting clues

This method serves as an early warning siren for aquatic invasive species. It enables species detection from the DNA left behind in the water.

Once Parks Canada knows invasive species are present using eDNA, staff can take steps to manage them and prevent their spread. This can include opening or closing water access points, like boat launches and beaches.

Some Parks Canada scientists also use eDNA to learn whether endangered species are in the waters.

Conservation staff at Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site collect and process eDNA samples from a lake

Aquatic scientists use eDNA to detect the presence of aquatic invasive species and endangered species in the water Case solved

The use of eDNA as a tool helps Parks Canada make decisions on what management and response efforts are needed. It also provides evidence that conservation actions are working.

Riding Mountain National Park

Water world

Invasive species are very hard to manage in aquatic ecosystems. Many water environments are connected. For this reason, it's hard to control the spread of aquatic invasive species.

Sometimes aquatic invasive species enter from headwaters that flow into a national park. Launching a boat that came from other waters can bring in small aquatic invaders or fragments of plants.

Unlike on land, we don’t always see aquatic invasive species. This is one reason that eDNA is such an effective tool for detecting aquatic invasive species.

Taking action

Parks Canada takes a lot of action to prevent and manage aquatic invasive species. Megan Goudie, Ecosystem Scientist with Parks Canada says “once an aquatic invasive species is confirmed, management actions have to be taken depending on the risk.”

Parks Canada works with and learns from many different people and organizations from across the country and around the world. It takes many people working toward a solution.

Parks Canada collaborates with:

- Indigenous nations and communities

- other federal departments

- the provinces and territories

- universities and colleges

- non-governmental organizations

- the public

Together, we use different methods for controlling aquatic invasive species. We share and adopt best practices. Some of these include:

- creating early detection and monitoring plans

- mapping their invasion

- managing their spread and removal, like building impassable barriers for invasive fish

- applying regulatory tools, like mandatory watercraft inspection stations

- restoring ecosystems after invasive species have been removed

- protecting species at risk and their habitat

Select images to enlarge

Your role in protecting aquatic ecosystems

Visitors to Parks Canada administered places play a key role in preventing aquatic invasive species and protecting species.

Here are a few ways that you can help:

- Stop aquatic hitchhikers. Clean, drain, and dry your watercraft, paddle board, canoe, toys, and all gear before and after use:

- Clean mud, sand, plant or animal parts from all items before leaving the shore

- Drain all water from watercrafts, trailers, and gear. Invert or tilt items. Open all compartments. Pull drain plugs

- Dry items completely before entering any river, pond, lake or stream

- Don’t let it loose! For the safety of our waters and the health of local ecosystems, it is illegal to release plants and animals into any Parks Canada administered site

- Date modified :

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)