Photo: Stefano Liccioli/Parks Canada

Bison and the power of partnerships

Protecting bison cannot be done alone.

Parks Canada works in partnership with many Indigenous communities to help bison grow and thrive. Bringing the bison back can rekindle the longstanding relationship between Indigenous peoples and bison. Learn how Parks Canada’s bison transfers have been key to this process. Jump ahead to learn how bison serve as a path towards reconciliation.

Bison decline

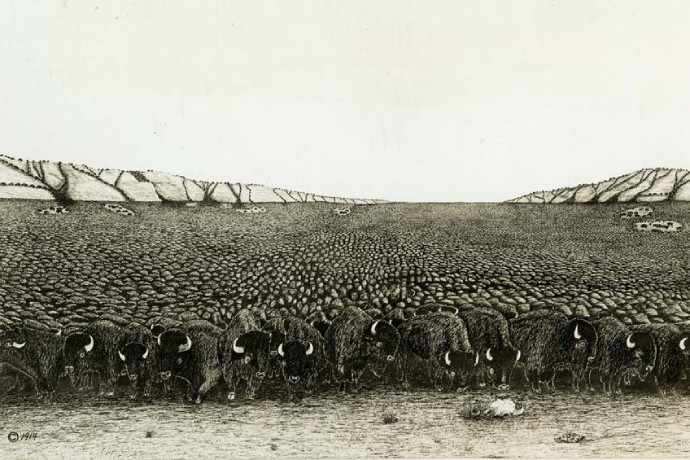

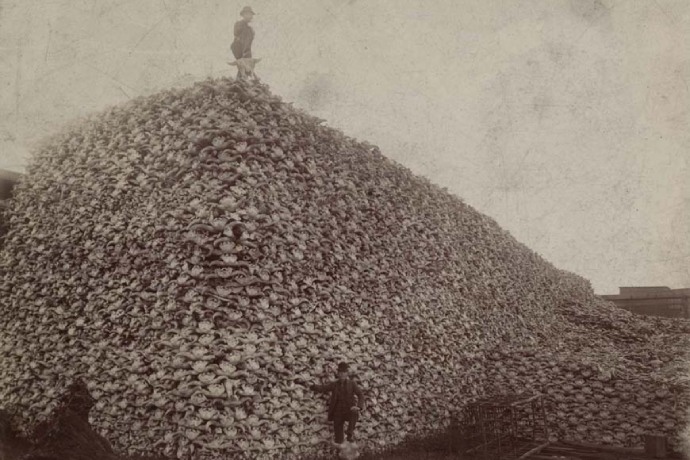

Bison are North America’s largest land mammal. Before European colonization, tens of millions of bison roamed many parts of the continent. By the late 1800s, their population was reduced to near extinction from overhunting and industrial demand. Only around 1000 bison remained.

Bison and the land

Bison play an important role in shaping landscapes as ‘ecosystem engineers’. Bison behaviours create conditions and habitats that can benefit many other plants and animals.

Bison waste incubates insect eggs and larvae. Many endangered prairie bird species eat insects. They benefit from the bison’s influence on insect presence. Endangered prairie birds also benefit from bison’s grazing patterns. Bison are helping Parks Canada manage the habitat of at-risk prairie bird species and their recovery.

Bison create “wallows” when they roll in the dirt to take dust baths. Wallows can fill with water when it rains, and provide important habitat for many prairie wildlife. Bison also spread seeds around as they travel. Birds use their fallen fur for nesting.

.jpg)

Parks Canada conserves the only two subspecies of bison in North America: Plains Bison and Wood Bison.

Plains Bison have a:

- large, bushy hairstyle on their head

- rounder back hump that sits directly over their front legs

- historic range as far south as Mexico, as far east as Florida, but were most common on the Great Plains

Wood Bison have:

- bigger and taller bodies

- smaller, pointier beards, darker fur, and hair that droops over their forehead

- a tall and triangular hump that sits far ahead of their shoulders

- adapted to colder climates, including northern Alberta, Alaska, the Northwest Territories, and Yukon

Bison are important for the health of natural ecosystems in which they normally occur. They also support many Indigenous cultural connections to the land and their ways of knowing.

Cultural connections with bison

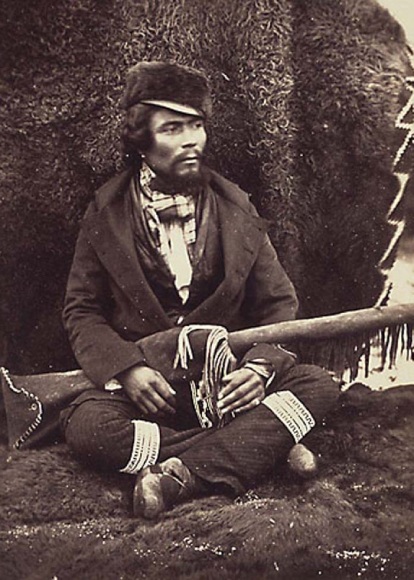

Bison have always been important in the lives of many Indigenous peoples in what are now the Prairie Provinces, British Columbia, Northwest Territories, and other parts of Turtle Island. Many Indigenous communities have long held deeply cultural and spiritual connections with bison. They have relied on bison for:

- food

- shelter

- clothing

- tools

- fuel

- weapons

- trade

- social and ceremonial purposes

Many Indigenous cultures continue to hold close relationships with their relatives—the bison. This includes for spirituality, food sovereignty, and social-economic development.

Parks Canada and bison

For over one hundred years, Canadian national parks have worked to maintain and restore bison herds for conservation. Parks Canada also works to uphold bison health and genetic diversity by maintaining disease-free conservation herds.

.jpg)

Parks Canada wildlife scientists are working with partners to restore healthy bison populations. Among other efforts, they are developing tests for detecting bovine tuberculosis (TB) and brucellosis. Early detection will help reduce transmission of these diseases. They are also working to develop a vaccine that will protect bison from getting bovine TB. Watch the video below from Wood Buffalo National Park to learn more.

Field Notes vlog: Restoring Healthy Bison Populations

Text transcript

[Parks Canada beaver logo]

Helicopter pilot fastens their helmet, preparing for liftoff.

[Text] Wood Buffalo National Park is home to the largest free-roaming, self-regulating Wood Bison herd left in the world.

Helicopter flies over a herd of Wood Bison running in the snow.

[Text] Wood Bison are vitally important to Cree, Dene and Métis in this region. The bison also play a key role in their surrounding ecosystems.

[Location Tag] Wood Buffalo National Park, Alberta

Todd speaks into the camera while a Parks Canada employee takes blood samples from a bison behind him.

[Todd] “So we’re here in lake one, Wood Buffalo National Park, taking some biological samples, blood samples, for developing some TB tests and vaccines. Things are going well, induction times have been pretty good on these animals. This is the first bull of the day.”

[Name Tag] Dr. Todd Shury, Wildlife Veterinarian

[Title] Field Notes: Restoring Healthy Bison Populations, Wood Buffalo National Park

A herd of bison stand together in the snow.

[Text] Bison transfers in the 1920s from Buffalo National Park have left many wood bison here infected with exotic bovine diseases: brucellosis and tuberculosis.

[Text] Parks Canada is working with researchers at VIDO-Intervac to develop a new vaccine and more sensitive blood tests to reduce disease transmission.

Camera approaches the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo Air Terminal building in Fort Chipewyan.

A Parks Canada employee approaches a bison that is laying on the ground in the snow.

[Todd] “So the first thing we do is check the level of anesthesia on the bison, make sure it’s completely out before we approach it, and Brian’s going to be pulling the darts… looks like he’s out.”

[Name Tag] Dr. Bryan MacBeth, Wildlife Health Specialist

A Parks Canada employee approaches the bison, carrying gear from the helicopter. The employee removes the tranquilizer darts from the animal.

[Todd] “We’re going to be checking the vitals, make sure he’s doing all right … what are we at?”

[Name Tag] Rob Belanger, Ecologist

Parks Canada employees conduct a series of tests on the bison and take its temperature.

[Rob] “87.”

[Todd] “87? Nice… that’s decent.”

Parks Canada employees place a red blindfold over the bison’s face.

[Todd] “Put a blindfold on him to reduce any visual stimulation. We’re going to hook him up on oxygen, then we’ll start taking our samples.”

Parks Canada employees hook the bison up to an oxygen machine, placing two clear tubes into the bison’s snout.

[Text] In the past, bison had to be captured multiple times or even killed to test for bovine diseases, which made detection difficult.

[Text] These new blood tests will be able to detect bovine tuberculosis with a single blood sample.

Parks Canada employees collect blood from the bison using clear syringes. Employees are wearing toques and parkas to protect them from the cold and snow.

[Todd] “So the whole reason we’re trying to get blood out of these animals—and we have to keep the blood at room temperature, which is extraordinarily challenging in the winter, when we prefer to capture them—is so that we can run what’s called an interferon gamma release assay and find out if these bison have been exposed to tuberculosis.”

Parks Canada staff, wearing plastic gloves, deposit blood samples into test tubes at a chemistry lab in Fort Chipewyan.

[Todd] “It’s a blood test, and we can run part of it back at the lab, back at Fort Chipewyan, and then the rest of that test is done back at VIDO-Intervac in Saskatoon. That’ll tell us whether this animal’s actually been exposed to tuberculosis.”

A beige GPS collar lays on the ground in the snow next to the bison. Parks Canada employees place the collar around the bison’s neck.

[Todd] “This is a GPS collar that communicates with satellites, gives us a position roughly every two hours. And we’re hoping they’re going to stay on for at least a year, but we will see. Wow, he’s like right out … but still breathing well.”

Parks Canada staff continue to take measurements, hair samples and other biological samples from the bison.

[Todd] “We’re going to collect hair samples from this bison for genetic analysis, but also for looking at heavy metals and contaminants, and we’re going to collect a fecal sample as well. This is the glamorous part of the job, eh, Rob?”

Bison wakes up and begins to stand. The helicopter takes off and flies over the bison, who has rejoined the herd and is running through the snow.

Todd is standing in the small chemistry lab at Fort Chipewyan. He shows viewers the lab equipment that will be used to process the biological samples.

[Todd] “So we’re back from the field now, and it’s time to process the samples that we’ve collected from the bison. We’ve got our hair samples, right here, going to use that for genetic DNA analysis, something we can archive for a long time. And we’ve got our fecal samples, and our blood samples.”

Todd shows the camera the test tubes containing the biological samples.

[Todd] “We’ve got two green-topped tubes, two serum tubes, and a RNA tube for doing some transcriptomic work.”

Todd handles the samples by inserting his hands into gloves inside a small sterile tent. The sterile tent allows him to handle the samples without contaminating them.

A scientist inserts the samples into a small incubator that sits on top of a desk in the lab.

[Todd] “We’re now going to incubate the blood overnight to produce what’s called interferon gamma. And that’s a kind of protein that’s released from cells, and if the bison have been exposed to bovine tuberculosis in the past, they’ll have higher amounts of interferon gamma in the cell the next day. And that’s going to basically tell us if those bison have been exposed to bovine tuberculosis.”

Todd prepares his test tubes with the blood samples, using gloved hands inside the sterile tent.

[Todd] “So now we’re going to drop some of this blood from these animals that we collected today. In the future, we’re also hoping to develop some sophisticated vaccines, for both bovine tuberculosis and brucellosis.”

Todd speaks to the camera standing outside the lab in Fort Chipewyan.

[Todd] “Well, we’re all wrapped up here in Fort Chipewyan, we’ve had a pretty successful trip, we captured about 18 bull wood bison over the past 10 days or so. We’re heading back, we’re going to process the blood samples we’ve collected at VIDO-Intervac, and find out how many of those animals were actually exposed to bovine TB. Overall it went really well, so we’re really happy with the way things went.”

Bison standing in the snow.

Approximately 70% of the bison bulls tested in Fort Chipewyan were positive for bovine tuberculosis.

Work to reduce these numbers will continue for years to come, through the collaboration of Parks Canada, industry, academia, and the Bison Integrated Genomic (BIG) project at Genome Canada.

When bison thrive, nature and the communities that surround them thrive as well. Learn more: parkscanada.ca/bison

End screen directing viewers to related videos.

Parks Canada Logo

Parks Canada wordmark

Establishing bison herds would not have been possible without the stewardship of bison by Indigenous peoples. In the late 1800s, two Indigenous ranchers managed the Pablo-Allard herd. These animals were among the last wild Plains Bison. The Government of Canada bought 700 of their bison in the early 1900s. The bison were sent to Buffalo National Park and Elk Island National Park. Lessons were learned from the operation of Buffalo National Park. The bison at Elk Island have since become the main source of bison stock for reintroduction projects.

Today, Parks Canada manages bison across the country. These sites include:

- Elk Island National Park

- Grasslands National Park

- Prince Albert National Park

- Banff National Park

- Waterton Lakes National Park

- Riding Mountain National Park

- Rocky Mountain House National Historic Site

Wood Buffalo National Park was established to protect the last remaining population of wild Wood Bison in North America.

Bison transfers at Parks Canada

Parks Canada is helping to restore bison back onto the land through the transfer of bison. Bison transfers help to increase the number of conservation herds in Canada and beyond.

The Agency has transferred over 3400 Plains and Wood Bison to conservation sites and other interested groups. Over 600 of these bison were transferred to Indigenous communities to support them in establishing their own conservation or cultural herds.

Photo: Stefano Liccioli/Parks Canada

Watch the types of bison that Parks Canada has transferred, and who has received them:

Transcript

Parks Canada Beaver Logo

A dark green map of Canada showing Parks Canada National Parks and Marine Conservation Areas appears, then quickly zooms in to focus on British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and the southern portions of Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut.

A timeline appears across the bottom, beginning at the year 1890 and ending at 2020+.

A legend in the top right corner identifies types of bison transfers. A solid green line represents Plains Bison, a dotted green line represents wood bison and an orange line in both solid and dotted form represent bison transfers to Indigenous communities (both Wood and Plains Bison).

Lines begin sprouting from Parks Canada places to other locations, representing bison transfers; some transfers land in other national parks, some land with conservation groups and some land with Indigenous communities.

The corresponding recipient of the bison transfers is shown scrolling along the top.

A “bison counter” at the bottom begins tallying the total number of bison transferred by Parks Canada to external groups.

The timeline moves slowly from left to right (the first transfer is sent from Banff National Park to former Buffalo National Park), revealing that the number of transfers is increasing each year over time.

Near the end of the animation, the “bison counter” reveals that the total number of bison transferred by Parks Canada to external groups is over 3000 between years 1909 and 2022 and will continue to increase.

Government of Canada logo

Parks Canada has made significant contributions to bison conservation and restoration in North America. Today, many bison herds exist across the landscape thanks to these transfers.

The historic return of bison

Bison had been absent from Grasslands National Park in Saskatchewan for over 120 years. Parks Canada reintroduced Plains Bison back onto the landscape as a large grazing herbivore in 2005.

Photo: Stefano Liccioli/Parks Canada

Bison provide visitors with a greater diversity of native plants and animals to see when visiting the park’s West Block. Watch the story of the bison return to Grasslands National Park.

Return of bison to Grasslands National Park

Text transcript

0:00 Bison went nearly extinct at the end of the 19th century.

0:06 Thankfully, they returned to Grasslands National Park in 2005.

0:12 The initial herd arrived from Elk Island National Park and consisted of 71 bison.

0:17 The herd’s reproduction rate is excellent.

0:21 The herd size is now kept between 300 and 500 bison.

0:27 Parks Canada researchers collect different samples from the bison.

0:33 These samples help scientists monitor the health of these animals.

0:38 This data is also helps maintain a herd structure similar to what would have been found in the wild.

0:46 Bison are recognized as ecological engineers.

0:56 Grazing is essential to the health of the mixed-grass prairie ecosystem.

1:01 Many species at risk benefit from the presence of the bison.

1:11 Thumbs up for the bison!

1:19 Like. Comment. Share.

Plains Bison were also reintroduced to Banff National Park in 2017 from stock in Elk Island. Watch the historic return of bison to Canada’s first national park.

Wild Bison Return to Banff National Park

Text transcript

0:10 My name is Karsten Heuer and I am the bison reintroduction project manager for Banff National Park.

0:18 My job is to orchestrate all the moving parts of trying to get bison from Elk Island National Park into Banff National Park.

0:28 Parks Canada's primary mandate is to ensure what we call ecological integrity, which means the health of the ecosystem.

0:35 And because something has been missing, North America's largest land mammal, part of our job is to try to bring it back.

0:42 And that’s what this is all about. It's about that effort.

0:47 From about noon today until about hopefully about noon tomorrow, so a 24 hour period

0:52 we are actually going to be doing an operation that has a lot different moving parts.

0:57 The first part is bringing the animals through the Elk Island corral system and chute system,

1:03 give them a tranquilizer, and then do some last minute changes to ear tagging.

1:08 And then we will start to load them in groups of three and four through the chute system

1:12 up the loading ramp, into the containers that we've modified.

1:16 They're basically seacans or shipping containers with ventilation in them and a few additions to the doors.

1:22 And then, we'll truck them for 400 km. That will then take us to the end of the gravel road, Ya Ha Tinda Ranch.

1:30 And then we will actually bring in a helicopter in tomorrow, a heavy lift helicopter

1:33 that's coming from the coast and that will pluck each individual crate off the flat-bed trucks.

1:39 One by one, over the ridge, about 20 km into the heart of the reintroduction zone

1:44 where we have a pasture fenced,

1:47 where we are going to hold them for the next 16 months, feed them, support them,

1:52 allow them to calve safely twice, and then do the release after they have anchored to that landscape.

1:58 and have adopted it as their new home.

2:13 There's been so much research, there's been so much consultation, like literally years.

2:18 We've got everything in place that we could have possibly thought of.

2:22 And really, from here on in, it's going to be up to the animals.

2:34 You know, we are talking about giving a species a second chance.

2:38 The seed that we are planting today, you can't almost imagine what it might lead to in 50 or 100 years.

Bringing bison back onto the land creates new opportunities for everyone to learn about the importance of these animals.

Managing bison at Parks Canada

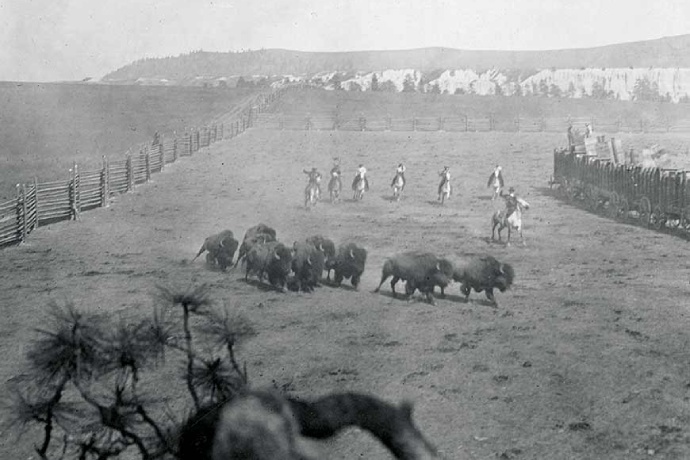

There are no natural predators to keep the bison herds within the carrying capacity of some national parks. Staff from Elk Island and Grasslands National Parks must remove bison to prevent overpopulation. This would lead to overgrazing, which negatively impacts bison and other wildlife in the parks. The need to remove animals creates opportunities to transfer bison to other groups across North America.

The aim of managing and transferring bison at Parks Canada is to help the overall numbers of Plains and Wood Bison in North America. Parks Canada transfers bison to groups that want to start or supplement their own conservation herd.

Photo: Stefano Liccioli/Parks Canada

Park staff manage bison following international guidelines for bison conservation herds. Actions taking place in key locations include:

- regularly monitor bison population size, sex, age structure to inform herd management

- perform herd health checks throughout the year, including disease testing to help maintain the herd health, where applicable

- collaborate with researchers on genetic testing to ensure their bison have a healthy and diverse gene pool at Grasslands National Park

Staff at Grasslands and Elk Island National Parks must gather bison for transfers when the populations are becoming too large. During this time, they also perform bison health checks. Staff reward bison with desirable food items near the handling facilities. The bison learn when and where these food items become available. This means bison arrive at the handling facilities when their presence is desired. In this way, difficult round-ups are avoided.

Bison and a path towards reconciliation

Parks Canada is learning and understanding more about its role in the path to reconciliation through the bison program. We have supported several Indigenous communities in re-establishing bison onto lands they manage.

These transfers help Indigenous peoples strengthen their cultural and historic connections with bison. They also support Indigenous-led social and economic opportunities around bison. Wanuskewin Heritage Park was one recipient of bison transfers.

When the bison come back, the culture comes back.

Watch the video to learn more about the bison transfer to Wanuskewin Heritage Park

Text transcript

0:06 There’s no place on earth like Wanuskewin Heritage Park.

0:14 What we’re hoping that the visitors will take away is the power of partnership.

0:19 We’ve had this wonderful partnership with Parks Canada

0:22 where we’re able to bring the bison back which strengthens our culture.

0:25 When visitors come here they get to see Indigenous culture in action,

0:29 they get to participate in curriculum programs around the bison,

0:34 and have an authentic experience that makes them better human beings.

0:42 The bison were there for our sustenance.

0:44 They, historically, provided everything we needed.

0:50 The bison are the iconic animals of North America.

0:54 They had a near demise, extinction,

0:57 very close to extinction in the early 1870s,

1:01 and by 1885 their population had gone from 26 or 30 million

1:07 down to less than a thousand.

1:09 So, that’s cataclysmic.

1:18 We move about 200 animals,

1:19 our goal is to keep the capacity of our herd between 300 and 500,

1:24 400 to 500 is optimal.

1:26 So, we send those animals on an order of preference

1:29 to other conservation herds, to Indigenous groups,

1:32 to educational institutions, and if we still have animals left over after that

1:36 they go to public auction.

1:43 But there are some practical implications here too.

1:46 When you go from 26 to 30 million

1:49 down to a thousand,

1:50 and then you start increasing the size of these herds,

1:53 because of restoration efforts,

1:55 there is what is known as a genetic bottleneck.

2:03 Being able to increase genetic diversity means sharing animals.

2:08 Like the arrangement we have with Grasslands

2:11 is one way of doing this.

2:13 I love the idea that Wanuskewin

2:16 would be a beacon,

2:18 a model for grassland restoration,

2:22 bison restoration, and to celebrate First Nation cultural history.

2:27 It’s a realization of the dream of elders from 40 years ago,

2:30 and we’re so happy to have that realization back.

2:33 There was a prophecy that had once said that

2:36 when the bison come back, the culture comes back.

2:54 I think that’s how

2:57 people can work together.

2:58 That’s an example that we have to take care of each other,

3:02 when things are down…

3:05 And then a better life.

Bison and The Key First Nation

The Key First Nation has coexisted with bison since time immemorial. The near extinction of bison created economic, spiritual and cultural losses for Indigenous peoples on the Prairies, including for The Key First Nation in Saskatchewan.

(Former) Councillor Chris Gareau has been committed to bringing bison back to The Key since 2018. He shared, “I’ve always had a passion for re-establishing bison on the landscape.” Chris worked with Parks Canada and The Nature Conservancy of Canada to transfer 40 bison back to his community. His vision was supported by others, including Councillor Clinton Key (now Chief), who secured important funds and a Regina-based steel company (EVRAZ) that donated pipes for the perimeter enclosure fencing.

Bringing bison back serves as a cultural resurgence for The Key First Nation. Bison have once again become a part of social and ceremonial events. Youth have begun to better understand their own connection with these animals, and with those of their ancestors.

It is saving the community. The youth see the possibility of having livestock on the land. For our people, bison provide opportunities for cultural rejuvenation, food security, and hope that we can change the damage that has been done for several hundred years.

The day the bison returned to The Key on December 23, 2021, around 200 community members showed up for the historic moment. “It was a positive union and experience for everyone—a warm feeling on a cold day,” Chris shared.

Watch the experience of bringing bison back to The Key First Nation

Text transcript

[Parks Canada beaver logo]

[Grasslands National Park landscape]

[A Parks Canada employee drives a side-by-side towards bison and spreads alfalfa cubes on the ground]

[Bison run across snowy plains and leaders from the Key First Nation raise their hands in the air, celebrating the return of bison to the landscape]

Today we're going to be baiting bison for handling

and bringing some of our reduction animals back to the Key First Nation

so that they have bison on their landscape for the first time in many years.

[Title: Field Notes, The Return of Plains Bison to The Key First Nation, Grasslands National Park]

[Ryan speaks into the camera while standing in front of the bison handling facility in Grasslands National Park]

Hi, I'm Ryan Hayes.

This is Grasslands National Park. I’m the Bison Operations Coordinator

[The camera pans across bison handling facility as the sun rises behind the building]

[Location Tag: Grasslands National Park, Saskatchewan]

and we're in Treaty 4 territory, homeland of the Métis.

[Ryan backs the side-by-side into a barn and loads the back with bags of alfalfa cubes, then heads to the river valley.]

Okay. I'm about to use the side-by-side you can see behind me and we're going to be loading some alfalfa cubes out of our building.

Bison seem to really like the cubes.

They see them as a treat and to them they’re Skittles.

On the way to the facility this morning, we noticed that there was about five family groups;

a couple of family groups were down in the river valley.

So that's where we're going to go this morning to try to bait and see some bison.

[Text: Before transferring the bison to The Key First Nation, the animals need to be gathered for a health check]

[A group of bison graze the grass amongst a vast open plain]

As you can see behind me, we're in the Broken Hills area and we have a family group of bison here, happy and healthy on their natural landscape.

[Bison grunts]

[Ryan speaks into the camera while standing in front of the bison as they graze]

[Text] Parks Canada staff are trained to work closely with bison. Never approach a bison in a Parks Canada place.

As the Bison Operations Coordinator here at Grasslands,

I work with the bison every day, so they are pretty familiar with me.

Typically, our tourists would not be this close to bison.

[Ryan drops alfalfa cubes from the side-by-side, encouraging the bison herd to follow, leading them towards the handling facility]

So part of the purpose this morning of what we're doing and baiting the bison is for our handling purposes.

This time of year we want them to come to a certain area, which is towards our handling facility, so we can gather the animals.

[Bison enter the indoor handling facility. Parks Canada staff collect hair samples and complete other tests]

We have to do our monitoring to make sure our animals are staying healthy.

Along with that, every two years we do a herd reduction so that they don't

[The camera moves along the ground through the grass]

run out of grass for themselves or be impacting the ecosystem

[A porcupine walks amongst the grass. A Black-Tailed Prairie Dog emerges from its hole.]

[Label] Porcupine

[Label] Black-Tailerd Prairie Dog

for the other species and animals that live here in Grasslands as well.

So we've finished baiting this group here in preparation for handling.

So we've used a couple of bags of alfalfa cubes to lead them in the direction of our handling facility.

And we'll be going on about our day and other tasks.

[Text] 5 weeks later…transfer to the Key First Nation

[A semi truck containing bison arrives at the bison release location]

[Chris and Clinton speak into the camera while standing in front of a teepee]

Hi! It's so nice to see all of the people here today.

[People gather near the bison release site, talking and hugging.]

My name is Councilor Chris Gareau and I'm a resilient Indigenous leader from the Key First Nation.

My name is Clinton Key. I’m a Band Councilor from the Key First Nation and bringing the people back together is what the whole intention of this project was.

[Someone serves bison stew from a crockpot]

So we're just sharing right now in some traditional bison cuisine.

The power of partnerships…this is a huge step forward in reconciliation.

[People celebrate as the bison are released from the back of the semi truck]

[people cheering]

It means togetherness, pride, spirituality, food sovereignty.

[Bison run through the snowy plains]

I believe everybody took something away from here today.

We did it. And we're happy.

[Chris pats Clinton on the back]

Oh, it was a great day.

[Text] Footage of bison release was generously provided by Jay-Cee Beass, The Key First Nation.

[Text] Returning bison to the Key First Nation supports Indigenous leadership in conservation.

[Text] It also provides an opportunity to renew cultural, historical, and ecological connections.

Learn more about bison conservation at Parks Canada: parks.canada.ca/bison

[Text] This video was filmed in 2021.

[Text] Check out other #ParksCanadaConservation projects.

The continued conservation of bison

Over a century of hard work and partnerships has helped bison regain their place on the landscape and within cultures. Yet, the work to conserve bison is not over. Bison transfers remain an important step in bison conservation.

Parks Canada continues to learn from past experience with bison transfers. We adapt protocols and handling facilities to better manage conservation herds. We continue to work with partners to restore bison back onto the land.

Parks Canada is honoured to support the restoration of cultural heritage of Indigenous peoples through bison transfers. We will continue to work in partnerships toward the survival and wellbeing of this iconic animal.

Learn more about bison projects happening across Parks Canada

- Plains Bison at Grasslands National Park

- Bison on the move at Grasslands National Park

- Watch bison through a live camera at Grasslands National Park

- Over a century of Bison conservation in Elk Island National Park

- Like Distant Thunder - Canada's Bison Conservation Story

- Bison blog at Banff National Park

- Bison videos from Banff National Park

- Bison at Waterton Lakes National Park

- Bison management and research at Prince Albert National Park

- Wood Bison at Wood Buffalo National Park

- Date modified :