Former Portage La Prairie Indian Residential School National Historic Site

The Residential School System is a topic that may cause trauma invoked by memories of past abuse. The Government of Canada recognizes the need for safety measures to minimize the risk associated with triggering. A National Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for former residential school students. You can access information on the website or access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-Hour National Crisis Line: 1-866-925-4419.

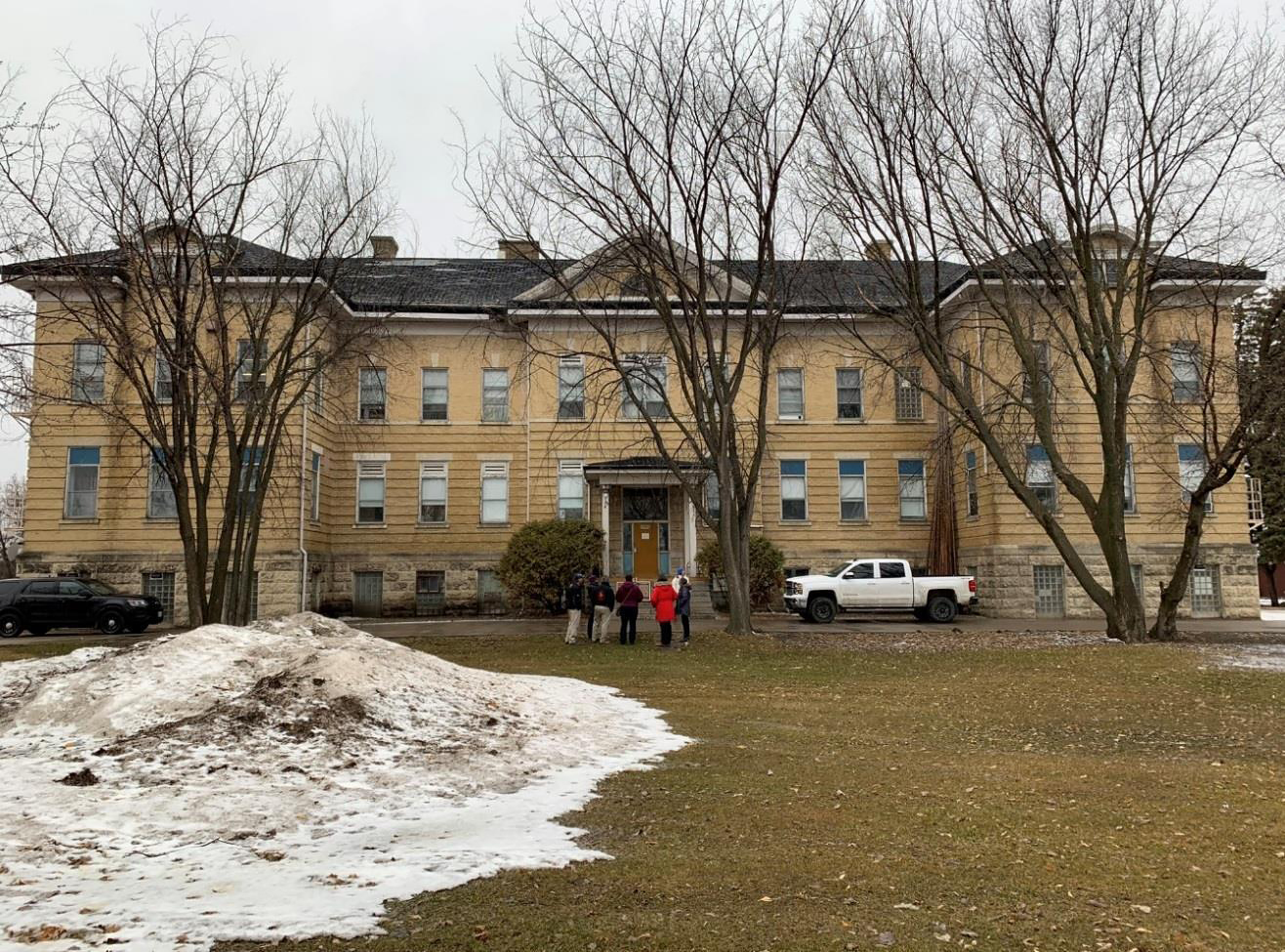

© Parks Canada / Allison Sarkar

The Former Portage La Prairie Indian Residential School was designated a national historic site in 2020.

Commemorative plaque: No plaque installedFootnote 1

Built in 1914-1915, the former Portage La Prairie Indian Residential School is located on Keeshkeemaquah Reserve, part of the reserve lands of Long Plain First Nation. This building was nominated for designation by Long Plain First Nation. Parks Canada and Long Plain First Nation worked collaboratively to identify the historic values of this former residential school, and the report on the building prepared for the Historic Sites and Monuments Board was co-authored by members of the First Nation and Parks Canada.

This large, three-storey brick building is a rare surviving example of residential schools that were established across Canada. It functioned within the residential school system whereby the federal government and certain churches and religious organizations worked together to assimilate Indigenous children as part of a broad set of efforts to destroy Indigenous cultures and identities and suppress Indigenous histories.

Children who were sent to the former Portage La Prairie Indian Residential School came from many First Nations and other Indigenous communities within Manitoba and elsewhere. There, they faced severe discipline and abuse, harsh labour, emotional neglect, the attempted suppression of their language and cultures, and isolation from their families and communities. Many children ran away, some to be later returned by force, and others engaged in acts of resistance such as secretly speaking in their own languages. The experiences of survivors of the Portage La Prairie Indian Residential School and other residential schools have affected members of these First Nations for generations.

The design of this three-storey building is typical of residential schools built in the early 20th century and reflects the norms of Euro-Canadian school design. Its imposing size, confining and institutional configuration, and isolated site generated feelings of dislocation, intimidation, and fear in the Indigenous children who lived there. The building was not culturally appropriate for children who were accustomed to living in familiar, open environments where they were free to explore.

The school closed in 1975 and six years later, the building and its surrounding lands were transferred to Long Plain First Nation to fulfill part of their treaty land entitlement. Since that time, the school has been readapted by the First Nation to serve a number of community purposes. It is now known as the Rufus Prince Building, named for a survivor of Portage La Prairie Indian Residential School who served in the Second World War and later became chief of Long Plain First Nation and vice-president of the Manitoba Indian Brotherhood. The building has been given new meaning by the community as a site of commemoration and resilience that keeps the legacy of the residential school era alive and educates the public.

Backgrounder last update: 2021-05-21

Description of historic place

The Former Portage La Prairie Indian Residential School National Historic Site of Canada is a large, three-storey brick building located on Keeshkeemaquah Reserve, part of the reserve lands of Long Plain First Nation, just outside the small city of Portage La Prairie, Manitoba. It was designed in an imposing hybrid Neo-Italianate style that was one of several historical styles used for residential schools during this time period. The former school sits on a treed lot and is set back from a relatively quiet road, with a small residential development and other buildings owned by the First Nation nearby, and farmland and Crescent Lake beyond. The school’s farmland once extended far beyond these boundaries. The formal recognition refers to the area that encompasses the current boundaries of the lot, essentially the treed lot surrounding the school.

Heritage value

The Former Portage La Prairie Indian Residential School was designated as a National Historic Site of Canada in 2020. It is recognized because:

- built in 1914–1915, the former Portage La Prairie Indian Residential School is a rare surviving example of Indian Residential Schools established across Canada. Managed by the Presbyterian and later United Church, the school functioned within the system of residential schooling in Canada, whereby the federal government and Christian churches worked together in an attempt to assimilate Indigenous children, convert them to Christianity, and isolate them from their families, cultures, languages, and traditions;

- children who were sent to the former Portage La Prairie Indian Residential School came from many First Nations and other Indigenous communities within Manitoba and elsewhere. There, they faced severe discipline and abuse, harsh labour, emotional neglect, the attempted suppression of their language and cultures, and isolation from their families and communities. Many children ran away, some to be later returned by force, and others engaged in acts of resistance such as secretly speaking in their own languages. The experiences of survivors of the Portage La Prairie Indian Residential School and other residential schools have affected members of these First Nations for generations;

- the design of this three-storey building is typical of Indian Residential Schools built in the early 20th century and reflects the norms of Euro-Canadian school design. Its imposing size, confining and institutional configuration, and isolated site generated feelings of dislocation, intimidation, and fear in the Indigenous children who lived there. The building was not culturally appropriate for children who were accustomed to living in familiar, open environments where they were free to explore.

The school closed in 1975 and six years later, the building and its surrounding lands were transferred to Long Plain First Nation to fulfill part of their treaty land entitlement. Since that time, the school has been readapted by the First Nation to serve a number of community purposes, and has been given new meaning by the community as a site of commemoration and resilience that keeps the legacy of the residential school era alive and educates the public.

The former residential school’s interior and exterior retain many features original to the time when it functioned as a school and residence however the cupola above the front entrance, and the verandahs at the rear of the building have been removed. In the 1980s, the school became the property of Long Plain First Nation and has been readapted for various community uses. This school building is valued as a site of resilience and part of it is dedicated to a museum documenting its history.

Source: Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, Minutes, December 2019.

The National Program of Historical Commemoration relies on the participation of Canadians in the identification of places, events and persons of national historic significance. Any member of the public can nominate a topic for consideration by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada.

Related links

- National historic persons

- National historic sites designations

- National historic events

- Submit a nomination

- Residential schools in Canada

- National historic designations

- Former Muscowequan Indian Residential School National Historic Site

- Former Shingwauk Indian Residential School National Historic Site

- Former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School National Historic Site

- Date modified :