Culture and history

Marconi National Historic Site

History

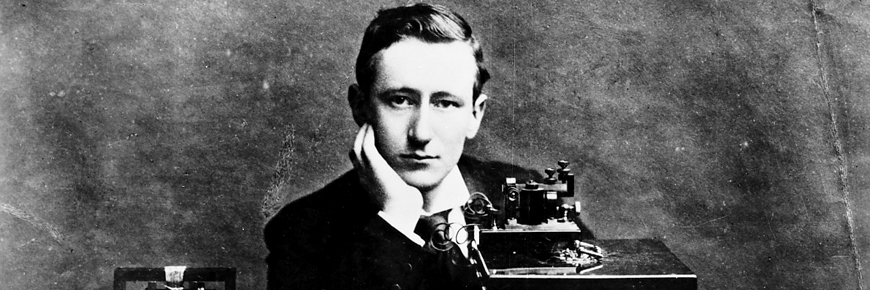

Late in October 1902, the Royal Italian Navy warship Carlo Alberto arrived in Sydney Harbour, arousing intense interest. Not only was the ship festooned with a bizarre array of copper aerials but on board was Signore Guglielmo Marconi, the scientific sensation of the day. Just a year before, on 12 December 1901, on the top of Signal Hill in St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador, Marconi had received a Morse code signal from his transmitter in England. It is difficult in today's world to conceive of the impact of such an event. Young, elegant and charming, Marconi was a member of an Italian family closely related to influential members of the British establishment. To these advantages were added a keen sense of scientific enquiry, enlightened by a spark of genius and, to top it off, a finely-tuned business sense that could close in on an opportunity like a steel trap.

Although the Anglo-American Telegraph Company forced Marconi to end his experiments in Newfoundland because it claimed he had violated its communications monopoly, within days he was in Ottawa dining with Prime Minister Sir Wilfred Laurier and the Hon. William S. Fielding, minister of finance and the most powerful Nova Scotian politician in Ottawa. In two more days, he came away with promises of $80,000 to finance a station to be located in Cape Breton, most likely on a windy plateau thrusting out into the North Atlantic from the edge of the booming mining town of Glace Bay. Why there? Unlike his scientific contemporaries, Marconi did not labour in dusty obscurity and his Newfoundland experiences had been followed by a fascinated public, including leading citizens of Cape Breton. Seizing the opportunity when he landed at North Sydney on 26 December 1901, fresh from his triumph in Newfoundland, they gave him a whirlwind tour of possible station sites near Sydney. Marconi liked Table Head and on a later visit in March announced his choice of the site. The owner, the Dominion Coal Company, turned it over to him and with his financing established with support from the Canadian government, the thing was done.

By the time Marconi arrived with the Carlo Alberto in 1902, the Table Head site was occupied by four spectacular wooden aerial towers, each over 200 feet in height, as well as the buildings containing the electrical equipment. After much experimentation, on 14 December, the station in Cornwall reported readable Morse code signals over a two hour period. The next night, the Canadian correspondent for the London Times, George Parkin sent a dispatch to England. This was followed by official messages to King Edward VII of Britain and King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy. Transatlantic wireless telegraphy had begun.

The following months saw almost feverish activity. The tenuous connection between Glace Bay and England was consolidated but every day new questions arose and new answers were found. It was one of the answers that led Marconi to abandon Table Head for a site on the other side of Glace Bay towards Port Morien, when it became necessary to increase the size of the aerial. The move, including the four towers, was made during the winter of 1904-05, but not before Marconi had begun to put his operation on a commercial footing. From Table Head, for example, under a contract with the Cunard Steamship Company, began regular wireless ship-to-shore communication that would revolutionize safety at sea. Here were laid the foundations that would soon ring the world with pulsing electrical waves.

By June 1905, the new station had established regular two way daylight communication with England. So reliable did this prove that in February 1908 unlimited public service was inaugurated. Within a few years, all the members of the British Empire were linked by Marconi stations and indeed, in the years between the two world wars, the Marconi Company held a near monopoly of world wireless communications. The commercial, as well as the scientific, success of Marconi's efforts was assured although his ceaseless search for improvements would eventually lead to the closure of the company's Cape Breton station in 1946.

- Date modified :